Data management for open access- 5 questions to ask about your data: Part 1 of The Data Lifecycle series

Editor’s Note: This is the first in what will be an ongoing series on data management, aimed to clarify the mysteries of data management for open access and support better scientific practices throughout the research and data lifecycle. The introduction to this series can be found here.

By Nicole Kaplan

Open access of data is increasingly a requirement (e.g. as a final goal or product) in scientific research. For example, federal funding agencies- such as National Science Foundation (NSF)- now require the dissemination of ‘data products’ that support research results1, while the Office of Science and Technology Policy, under executive order by President Obama, requires more broadly to “make government-held data more accessible to the public and to entrepreneurs and others as fuel for innovation and economic growth.”2 These goals are intended to accelerate the process of applying scientific understanding to solve real world problems.

These goals are intended to accelerate the process of applying scientific understanding to solve real world problems.

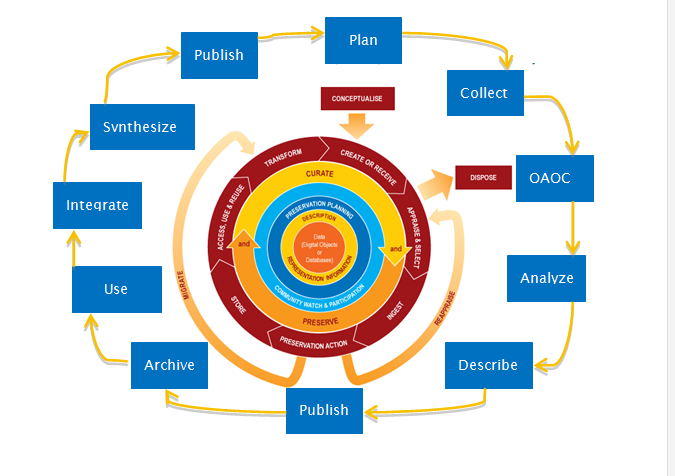

Today scientists must consider how their data will be discovered, accessed, re-used and cited by other scientists and document methods for meeting data management requirements. It is better for scientists to consider ways to manage their data in the process of doing research, as opposed to leaving all the work until the end of a project. The Data Lifecycle is a useful model for just that! It incorporates several approaches that enable successful data management with the end goals being data curation, appraisal and re-use (Figure 1).

How can we, as scientists, improve our data management practices, align them with steps in the Data Lifecycle and produce data for open access? How do we preserve and share ‘data products’ (i.e. carefully sorted and organized scientific data prepared for open access) through institutional and domain-specific digital repositories (e.g. within university libraries, and others listed at the end of this post), and with sufficient metadata (a.k.a. information about the dataset, such as how and when it was collected)? Where shall we begin?

As a data manager for the Natural Resource Ecology Lab (NREL), I help design and implement policies and procedures to ultimately make NREL data more findable and useable. I find the notion of ‘packaging’ data a useful idea; it implies that a data file (e.g. spread sheet, shape file, coded transcript) is tightly coupled with metadata (i.e. data about the data) and supporting documentation that will allow the data file to be found and understood in the future.

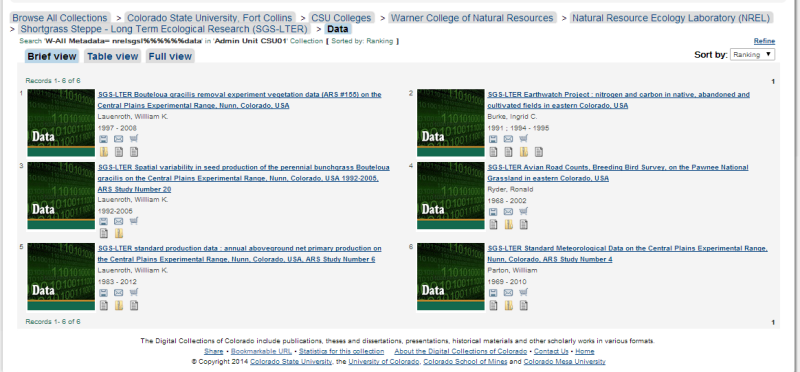

In this post, I share definitions and approaches to packaging data, drawing from my experience with curating several datasets from the Shortgrass Steppe Long-Term Ecological Research Project (SGS-LTER) and the Advanced Cooperative Arctic Data and Information Service (ACADIS). Implementation of standards within our SGS-LTER data packages, which are now curated by the Colorado State University Libraries, position them to be interoperable (or programmatically accessed by machine) with the Network Information System of the US LTER and the International Biological Information System, here at NREL. Open access and interoperability between repositories affords people various opportunities to find data and leverages the networked infrastructure of the web. In other words, using these types of systems and standards, scientific data can be found more easily.

In other words, using these types of systems and standards, scientific data can be found more easily.

In the following section I list 5 key questions to ask about your data, and define the concepts of data and metadata that will allow data packages to be prepared for submission to repositories. We are still learning about and adopting best practices for managing data within our systems. I look forward to expanding our tools and capacity for data curation with our partners at CSU and beyond.

Data management for open access- 5 questions to ask about your data:

- Are they data or a dataset? These concepts are used interchangeably, but it is important to define as is the format of the data files (e.g. tabular files as tab delimited or proprietary Excel files, image files, audio, free text, or within a geodatabase, etc.). Do your data make up a collection, which may be referred to as a dataset or does your dataset include a data table and metadata? The way you conceptualize your data and the types of data you are collecting or working with, their properties, such as file type, size, organization, and attributes are important components of the data, which should be documented in any data management plan.

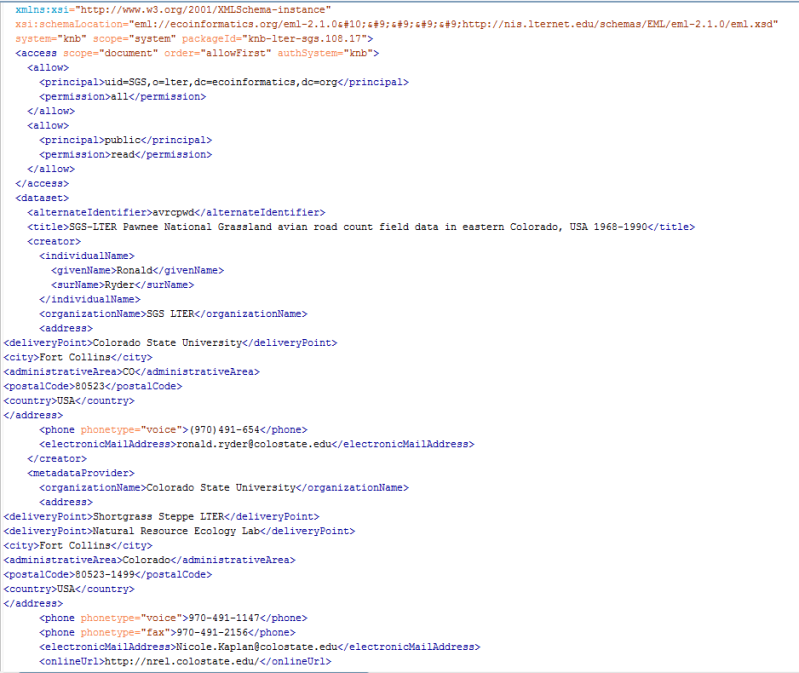

- What are the metadata? Metadata are referred to the “data about the data”, which sounds a bit redundant, so you may want to consider the metadata as the information necessary for someone to use the data and to catalog it within a repository. That someone could be a colleague or advisor with whom you are sharing the data or an interested member of the community who finds and downloads the data online. It is useful to provide the -who, what, where, when and how- of what you are describing as a human-readable document. Data discovery or automated access requires machine-readable, structured metadata. For this reason, metadata standards are being established and adopted by scientific research communities and tools are being developed to create structured metadata. When submitting a data management plan for a research proposal, one should have some candidates of metadata standards and resources listed in the plan. Here are some examples:

- Ecological Metadata Language (Figure 2) has been developed for data resources created in ecology. See the Knowledge Network for BioComplexity for tools to create EML.

- Dublin Core is a metadata specification that is a simpler metadata schema than EML and is used in library sciences. It has been adapted by other communities, e.g. for biodiversity data with Darwin Core. Dublin Core has 15 basic elements that can be expanded.

- Darwin Core had been adapted from Dublin Core for biodiversity and taxonomic data. See the GBIF Integrated Tool Kit for support with Simple Darwin Core and management of more complex metadata or larger datasets.

- Do I need simple or rich metadata? A data package can be prepared for submission to an institutional or domain related repository. The data and metadata may be coupled within the same file, or related with linked but separate files. The metadata may be embedded by adding columns with standard header names to your tabular data; Darwin Core (i.e. for biodiversity occurrence date) refers to this as simple metadata. The advantage to this arrangement is the metadata will be in-line with the data. There is little chance for separating the data from the metadata. However, containing metadata within columns limits the amount of rich information, which can be provided (e.g. an abstract or methods as free text).

- How can I package data rich metadata? Some examples of data packaging include creation of a single informational document, compression of various metadata documents within a zipped folder, or content in a community adopted metadata standard. Three examples are provided:

- Documented Data Package in the ACADIS: metadata are documented using a template for a “readme” file in Microsoft Word. ACADIS requires rich metadata, which can be provided in a free-text format or human-readable. They require details about the data including an overview of the data, a geographic bounding box of the origin of the data, and descriptions of file types organization, instrumentation, methods, references, and more. ACADIS is an data repository for archiving data collected in the arctic, and represents an example of using a simple human-readable approach for creating a rich metadata package. ACADIS repository staff will upload information from the word document into their structured database system.

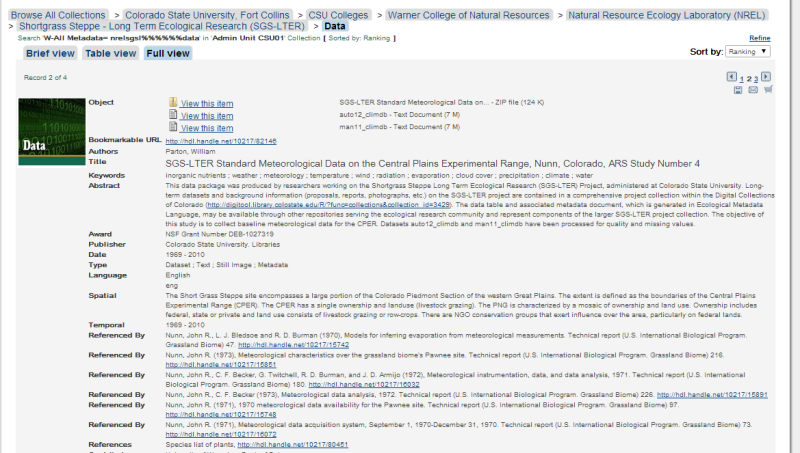

- Zipped Data Package of the SGS-LTER in the CSU Institutional Repository: a collection of objects that includes two kinds of items: some number of data files in a non-proprietary format (e.g. .txt, .csv) and a basic metadata folder (zip format) that contains the minimum descriptive information necessary for a basic understanding of the data files (Figure 3). The basic metadata folder at a minimum contains a Readme file (.pdf), but may also contain a file with variable and unit definitions (also as .txt or .csv), and related supplementary files such as photographs of plots (jpgs), digital datasheets (pdf) or site maps (pdf).

- Standard Data Package for the LTER Network Information System: a set of data and its associated metadata where the metadata is represented in the extensible markup language (XML) that is compliant with the EML schema and is “complete” with regard to metadata quality and content and provides “unfettered” access (in the machine accessible sense) to data, as a direct reference to the data through a unique and persistent identification protocol, such as HTTP or FTP). (accessed 4/3/2014)

- Where will my data package “land”? When a data package gets ingested into a repository, it is now common practice for data to be served from a landing page. A landing page is a web page that serves as an online location to ‘land’ and where information about data or digital objects may be found, including a ‘Readme’ file and documentation cataloged in the repository; there may be links to one or more data files and supplementary information. A landing page is a complex object that provides context for the data by grouping together files that are related to each other. It also may be assigned a persistent identifier (e.g. Handle or DOI), which can be cited when data are accessed and re-used (Figure 4).

We should be thinking about data and data packaging as it relates to the vision for an integrated sustainable cyberinfrastructure to support our scientific work. Baker and Yarmey (2009) developed a useful metaphor of a web-of-repositories, which originates with the creation of a data package locally, and affords a scientist in a remote location to access and re-use the data as long as there are adequate metadata documentation! Institutional repositories, such as CSU Libraries, domain-specific repositories, such as ACADIS and LTER NIS, and data replication and aggregation networks, such as DataONE are contributing to building out the broader vision for a web-of-repositories, where information can be discovered, disseminated and accessed from multiple locations. When we are creating and submitting our data packages, we should consider approaches that will improve discoverability (e.g. descriptive data set titles, keywords, and abstracts) and increase interoperability (e.g. structure metadata) of ecological data and information.

1Accessed 1/27/2014 from (http://www.nsf.gov/bfa/dias/policy/dmp.jsp)

2 Accessed 1/27/2014 from http://www.whitehouse.gov/administration/eop/ostp and Check Out the YouTube Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n603rEnEGXA#t=3

Baker, K. S., & Yarmey, L. (2009). Data stewardship: Environmental data curation and a web-of-repositories. International Journal of Digital Curation, 4(2), 12-27.

Baily, S. et al. (2014) ISTec Data Management Committee Findings and Recommendation. Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO.