Why diversity matters: the importance of racial and ethnic equality in conservation

By Kate Wilkins

“I just don’t understand why we still need to talk about bringing different races and ethnicities into the National Parks. I don’t know, it just doesn’t seem that important.” Funny you should say that random person that shall remain anonymous. I whole-heartedly (and respectfully) disagree.

I heard this statement after a series of panel discussions I helped organize entitled, “Black Conservation Movements: Engaging Black populations in national parks and protected areas,” and “African American Experiences in Nature.” The panelists discussed challenges and barriers to engaging African Americans in national parks and protected areas, and the lack of diversity among park service employees.

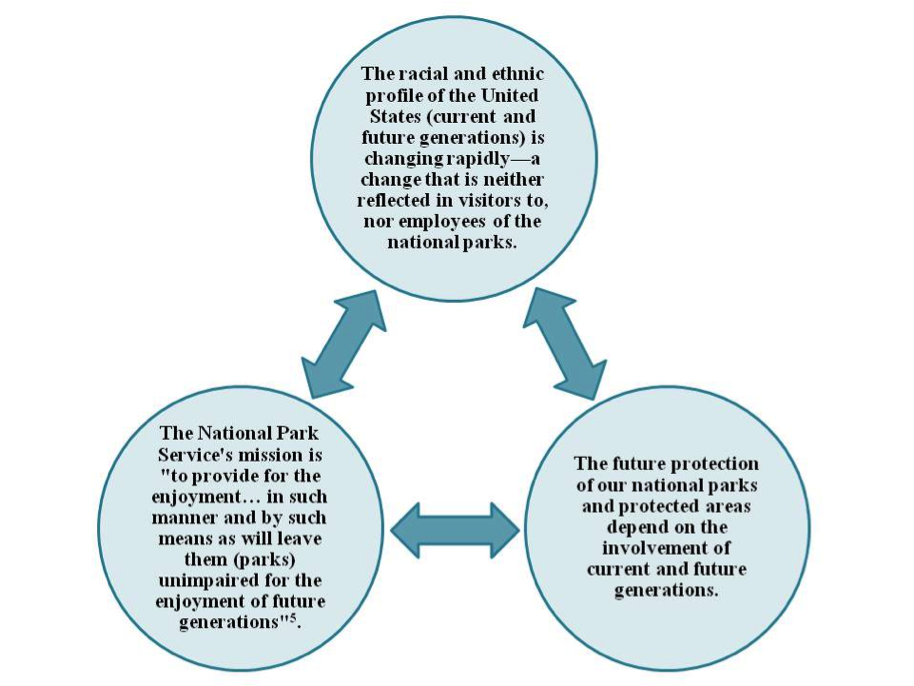

The ever-pervasive question in this discussion is WHY. Why should people care about this issue, especially if people think it doesn’t affect their lives? Anyone interested in the future of protecting our national parks, open spaces, and environment should care about increasing the participant diversity of those who protect our outdoor spaces. I hope to answer more of the “Why” in subsequent paragraphs.

The demographics of the United States continue to change rapidly. The U.S. census bureau estimated the 2012 U.S. population at around 313 million people. Figures 1 and 2 (below) both show the breakdown by race and ethnicity for 2012 and the percent change between 2000[1]-2012[2] in race and ethnicity, respectively.

*Hispanic or Latino is a cultural identity or ethnicity, and can include people of any race (White, Black or African American, American Indian/Alaska Native, or Asian). The other races on the graph represent that race only, and are not Hispanic or Latino.

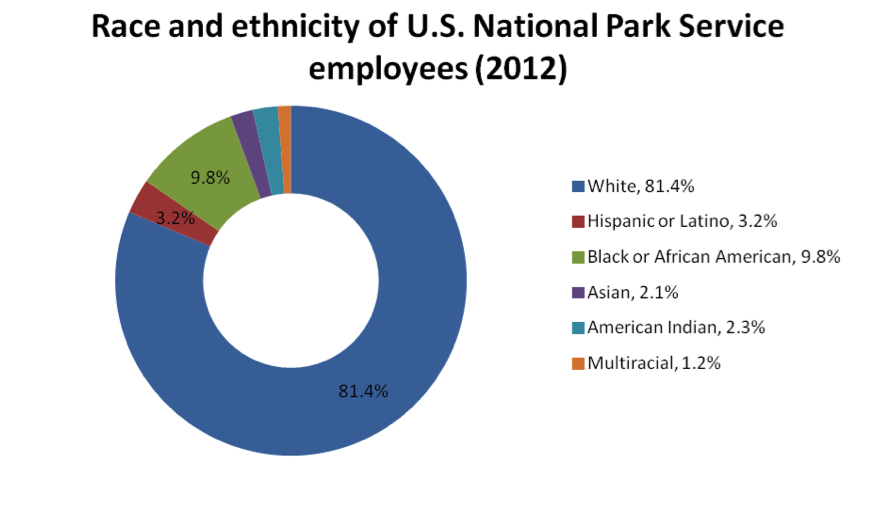

This survey revealed an imbalance of who is visiting U.S. National Parks, as well as the barriers[4] to visitation. Certain organizations, such as the Rocky Mountain Sustainability and Science Network (RMSSN), are dedicated to breaking down these barriers and engaging a more diverse public. Every summer, the RMSSN hosts a summer academy in the Grand Tetons to engage undergraduate and graduate students from a wide variety of cultural backgrounds and academic disciplines to network with people working at the National Park Service (NPS), Nature Conservancy, Bureau of Land Management, and universities. One goal for RMSSN is to connect students with potential internship and employment opportunities with the NPS to address the lack of diversity in employees at the National Park service, reflected in Figure 4 (above). Due to the changing demographics of the U.S., employing people from different backgrounds is not only important for the future sustainability of our National Parks, but also for creating a cycle that encourages more visitations from a wide variety of cultures!

Let’s review:

The responsibility to increase diversity is not only on the shoulder of National Parks. Mentors, the media, communities, secondary schools, universities, and organizations geared toward outdoor activities need to work together to encourage people from various racial and ethnic backgrounds to explore, learn about, and develop an appreciation for outdoor spaces. Continuing these discussions and collaborations could bring a new era of equality in the U.S. conservation legacy. I will conclude with thoughts from Teresa Baker, the Founder of the African American National Park event, and panelist for “Black Conservation Movements”, who had this to say about engaging a more racially and ethnically diverse public in the National Parks system:

The responsibility to increase diversity is not only on the shoulder of National Parks. Mentors, the media, communities, secondary schools, universities, and organizations geared toward outdoor activities need to work together to encourage people from various racial and ethnic backgrounds to explore, learn about, and develop an appreciation for outdoor spaces. Continuing these discussions and collaborations could bring a new era of equality in the U.S. conservation legacy. I will conclude with thoughts from Teresa Baker, the Founder of the African American National Park event, and panelist for “Black Conservation Movements”, who had this to say about engaging a more racially and ethnically diverse public in the National Parks system:

“Race matters, but customs do as well. When we grow accustomed to something we tend not to feel a need for change or even see the need for change. I think this is the larger of the problems we face when it comes to getting people who are already invested in our outdoor spaces, to see the absence of people who are not. As human beings, we gravitate to that which is comfortable, without realizing the impressions we leave, when we ignore all others. One of the divides we face in diversifying the outdoors is the notion that the lack of diversity is not an issue. To only hear the debate about this issue from organizations such as the NPS, only extends the debate when change does not happen.

I relate this issue to Brown v. The Board of Education, integrating black faces into a white school system. It was obvious and accepted that schools were purposely segregated and desegregating them was met with anger and hostility. The majority saw this as an infringement upon their rightful place and forced integration was not going to be an easy task. So, when I hear there is not a need to act on the issue of diversity in the outdoors, it leaves me dumbfounded.

The lack of black and brown faces in our natural spaces is an issue that many are not comfortable with addressing. The longer it goes unaddressed by those who simply say ‘it’s not an issue’ will only widen the gap of interest by people of color in the conversation on conservation. The need for greater involvement in protecting our open spaces grows every day; yet, the faces at the table remain the same.”

[1]Percent change in race and ethnicity for the U.S. population in 2000

[2]Percent change in race and ethnicity for the U.S. population in 2012

[3]Race and Ethnicity Demographics of National Park Service employees in 2012 from a 2013 report (Figure 4) taken from “The Best Places to Work in the Federal Government”

[4]More than 50% of African Americans and American Indians and more than 40 % of Hispanics and Asians agreed with statements, such as “The hotel and food costs at National Park System units are too high” and “I just don’t know that much about NPS units”. Around 54% of African American and 43% of Asians also agreed with the statement, “It takes too long to get to an NPS unit from my house.”

[5] National Park Service Organic Act of 1916 (39 Stat. 535, 16 U.S.C. 1.)

A note from the author:

In addition to RMSSN, check out these organizations that are working to get different groups into the outdoors:

American Latino Expeditions: http://www.alhf.org/alex13

GirlTrek: http://www.girltrek.org/

Outdoor Afro: http://www.outdoorafro.com/

Also, this is a great piece about the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation working with the Park Service to take over part of Badlands National Park to manage as the first tribally managed national park in the nation: http://www.npr.org/2012/05/25/153723299/s-d-tribe-poised-to-take-back-part-of-badlands

Kate Wilkins is a PhD student in Ecology at Colorado State University. Kate is Hispanic/White: her mother and family escaped from Cuba after Fidel Castro rose to power in the 1960’s, and her father’s family has Dutch roots. She has many interests, which include increasing the participation of underrepresented groups in science and conservation, as well as studying how climate change affects the interactions between people and nature.